For more, watch E:60's story, "Heir McNair," on Sunday at 9 a.m. on ESPN, or stream it on WatchESPN.

Her husband would have done things differently. He probably wouldn't have spent most of the summer dreading this moment, standing in front of a college dorm, trying not to cry.

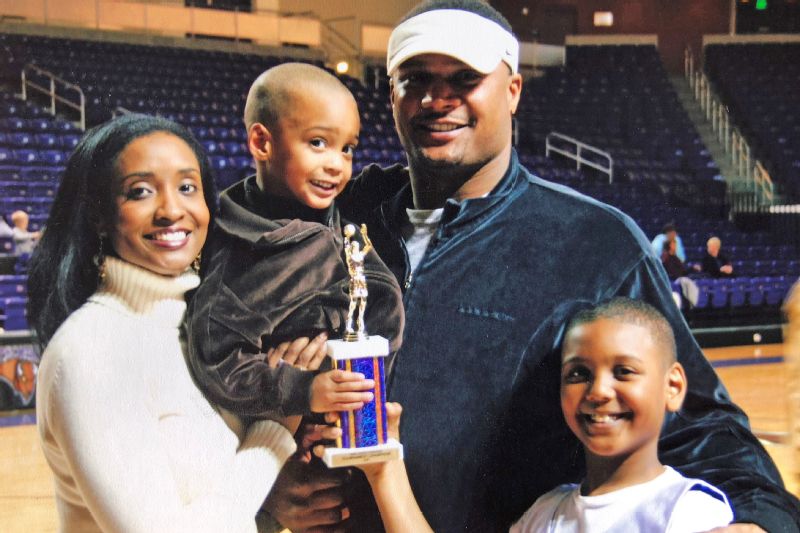

He'd handled everything -- the bills, the taxes, the boys' baseball swings -- until it was just her. And them. But this moment in front of the school is a good one. Nine years after Mechelle McNair's world caved in, her oldest son, Tyler, is going to NYU on an academic scholarship. He didn't just turn out all right. He's going to kick the world's ass.

They are best friends. Maybe they would have been anyway, had Steve McNair not been killed. Tyler tells her everything, even the stuff that can get him grounded. In happy times, they belted out SWV songs in Mechelle's little, red, two-seater Mercedes, his tiny head bobbing to the music. She once took him on a girlfriends-only trip to the Bahamas, and if anyone took issue with it, well, tough. Tyler was her road dog.

In the worst times, she kept both of her little boys beside her in bed, where she could keep them close and safe.

Mechelle is 45 now, and she does not look old enough to be dropping a son off at college. She was slow to trust after her husband's death and never remarried. She already had two men in her in life: Tyler, 19, and Trent, who just turned 14.

They carry pieces of Steve, from Tyler's mannerisms to the way Trent calls people "Buddy." But now one of them is leaving, and Mechelle is just trying not to lose it. The boxes are unpacked, the dorm room is clean, and there is nothing else to do but say goodbye. They hug, and Tyler wants to tell her something before she goes back home to Tennessee. He says she needs to go out more, to have fun sometimes. It surprises her and forces her to ask the inevitable question: Who am I when my kids are grown and gone?

"I look at Tyler," she says, "and he knows exactly what his passion is.

"What's my purpose? What's my passion?"

Heir McNair

E:60 sits down with former Titans QB Steve McNair's wife and son Tyler, who describe their feelings when they discovered Steve had been killed.PAUL SPINELLI/AP PHOTO

ON THE MORNING of July 4, 2009, Mechelle McNair woke up with a crushing headache. She stood up, the pain radiated from the right side of her skull, and she had to lie back down. She noticed her husband wasn't home and made a number of phone calls trying to find him. Nobody knew where he was.

She got on the elliptical machine, hoping some exercise would get rid of the headache. It would not go away. She would wonder, later, about signs.

Her mother, Melzena Cartwright, saw the news on TV. Years ago, after Cartwright lost her own husband, Steve had told her to pack her bags and come live with them. When news of his death flashed on the TV screen, Cartwright rushed through the house to Mechelle's room. Mechelle had just found out. "Mama," Mechelle asked, "do you think it's true?"

Steve McNair was born on Valentine's Day, and he died on the Fourth of July. The enormity of his death cannot be overstated. Here was an NFL quarterback one season into retirement, a former co-MVP and a Super Bowl participant, murdered.

Twitter wasn't a factor yet, but there were plenty of media outlets to feed off of the stunning story of a Tennessee football hero killed by 20-year-old Sahel Kazemi, a woman with whom he'd been having an affair.

The Metropolitan Nashville Police Department ruled it a murder-suicide, concluding that Kazemi shot McNair four times -- twice in the head -- in the early morning hours of July 4, most likely while he was sleeping on the couch of his rented condo. Kazemi then lay down beside him and fired a bullet into her head. The tabloids fed off the story and ran photos of McNair vacationing with the young waitress and texts they sent to each other in their final hours.

Everyone wanted to know what Mechelle was feeling. How do you think she was feeling?

"I didn't know about her at all," Mechelle says. "You're going to have people who say, 'Oh, she knew.' Did I know about some other people and some other things? Yes. But did I know about her? No, I did not."

Initially, she did not believe her husband was dead. The man who had taken epidurals and basically crawled around in pain six days a week but somehow played football on Sundays couldn't be gone. She wanted to see him so she could help him.

When it hit her, she fell to the floor, screaming. Her children had never seen her like that.

Tyler, who was 10, started crying. He ran to the kitchen and got a knife. He said he couldn't live without his daddy and wanted to kill himself. Mechelle grabbed him and told him to stop. She said she couldn't bear to lose both of them.

How was she feeling?

Just 24 hours earlier, McNair had taken his sons fishing. It was a good day for two little boys who saw their dad as a superhero. He cleaned the fish when they got home that night, washed his truck and began to doze off on the couch.

But his phone kept ringing. He told Mechelle that the alarm was going off at his restaurant, but she knows now that Kazemi was probably the one who called.

He said he had to go, and kissed the boys goodbye.

"Don't go," Tyler and Trent told him.

McNair said he loved them. He kissed Mechelle and told her he loved her, too.

"I'll be back in a little while," he said.

![]()

Nearly 5,000 people mourned McNair at Reed Green Coliseum on the campus of Southern Miss. At the time, it was considered one of the biggest funerals in the state. Trent, pictured right, was 5. He leaned on his mother, Mechelle, and Tyler, at left. GEORGE CLARK/HATTIESBURG AMERICAN POOL/GETTY IMAGES

THE VISION OF a 10-year-old boy holding a knife was like a cold bucket of water in the face. From that moment on, she could not let her children see her break down. She would go to her room, door closed, and sob. She would lean on her friends, who dropped everything to be with her in Nashville, or cry to her aunts and uncles. But her sons were terrified and confused. She would not lose it in front of them.

Steve McNair was buried on a Saturday in his home state of Mississippi. Brett Favre and Ray Lewis and Jay Cutler showed up for the funeral. Trent, who was 5, rested his head on his mother's lap during the service.

She tried to explain to the boys what had happened, the best she could, but Trent wanted to read about his father in the paper. He ran his finger through the print and sounded out the words he knew. He asked how somebody could do this to his daddy.

Mechelle told him she didn't know. She is a spiritual woman who thanks God every morning for waking up and for allowing the rest of her family to wake up, too. God got her through this, she says. God and her friends and family who cooked and took the kids swimming and handled everything. She is thankful for that last day McNair had with the boys and for that night when they argued and made up.

"At the end of the day, that's my husband," she says. "I loved him. I still love him. He was human. He made a mistake. Nothing's going to change how I feel about my husband. He took care of us. He loved us. I do know that. Regardless of how he left here, I know he loved us.

"I can't say that I didn't have my bitter moments. And that I still don't sometimes. But I'm not going to hell blaming somebody or having the hate and animosity in my heart. I'm not going to do it."

THEY MET AT Alcorn State, a historically black college in rural Claiborne County, Mississippi. The closest town, if you want to call it that, is Lorman, a community with one known claim to fame, the Old Country Store, which serves fried chicken that people drive hours for. Mechelle didn't particularly want to go to such a tiny school. She had hoped to go to Southern Miss. But she put off doing the paperwork, and Alcorn was the school that offered her a scholarship.

Freshman year, she had a human anatomy class with McNair, and he spent most of it staring at her. She made faces at him to try to get him to stop. He was quiet until you knew him, and he waited a while to talk to her. The fact that he was the quarterback everyone on campus was talking about held no currency with Mechelle. She wasn't into sports, and she already had a boyfriend.

But McNair was persistent. He sat behind her in class and constantly flirted. He did annoying things, peeking at her test answers, sticking his giant feet on her book bag. Eventually, he grew on her. To Mechelle, he was sort of a gentle giant, romantic enough to hide an engagement ring in a piece of strawberry cake, country enough to skin a deer and cook it up for his teammates.

Before she met McNair, Mechelle never thought she would get married. She had plans. She wanted to be a doctor and wanted one child, but she didn't think much about a partner. She never imagined she'd leave Mississippi after college to move to Houston with a man who had just been selected at No. 3 in the NFL draft. But plans change. They got married in Vicksburg, Mississippi, in 1997, and a year later, Tyler came along.

Although she didn't grow up playing sports, Mechelle quickly acclimated herself to the life of a football wife. Ex-linemen tell stories about how she used to sit in the stands and yell at them to protect her husband. She had plenty to cheer about by the time the franchise moved to Tennessee in 1997. McNair threw for 3,228 yards and 15 touchdowns in '98, and he led the Titans to the Super Bowl a year later.

He was known as one of the toughest men in football, playing through myriad injuries.

"He would just come home and be, like, dead," Tyler says. "He didn't want to do anything. He didn't want to watch TV, didn't want to eat anything. He'd say, 'I just need some rest.'"

There were good times, too. Times when the family would pair up in teams and wrestle, Mechelle and Tyler on one side; Trent and Steve on the other. Times when McNair would take the boys out on his motorcycle and they didn't even need to talk.

"Steve was a good person," Mechelle's mother says. "He was a good dad. There wasn't anything those children wanted that he didn't get for them."

![]()

Though McNair was an NFL quarterback, he never wanted to force football or sports on his children. He told them to find something they loved and to do it well. COURTESY MECHELLE MCNAIR

HE WAS 36 when he died, and he had just opened Gridiron9, a catfish-and-burger joint in north Nashville. In his last days, McNair seemed overwhelmed at times, almost as if he was at a crossroads, Mechelle says. He was still trying to figure out his world outside of football.

He split time between his home in Nashville and his farm in Collins, Mississippi. He felt comfortable in the country, near his siblings and his mother, Lucille. (McNair also has two older sons from previous relationships.) The transition from football player to businessman was not smooth. The last full conversation he had with Mechelle centered on the restaurant's nightly receipts constantly being off and her desire to help. She was so happy at the end of their talk, when he said she could attend the next employee meeting. McNair had dreams of his restaurant becoming a chain. A few months after his death, the restaurant was sold.

He did not have a will, creating a painful mess that dragged on for years. In 2011, a legal spat between Mechelle and Lucille over property in Mississippi played out in the local news media. Mechelle had always considered herself a private person. But after Steve's death, the most intimate details of her life were fodder for public consumption. Conspiracy theorists flooded the internet and airwaves. A "True Crimes with Aphrodite Jones" episode filmed in 2013 even pointed suspicion at her. (She was never a suspect). That same show aired as a rerun last week, on the night of the Super Bowl.

Aside from kid functions and dinners out, she lived the life of a homebody. She had one job: to raise their sons.

Comments